NEW eBOOKS AVAILABLE IN 6 FORMATS

Adobe acrobat = PDF

HTML = .htm

Kindle = .mobi

MSReader = .lit

Nook = ePUB

PALM = .pdb

|

HOME >> Product 0646 >> Darian Bridge>>

|

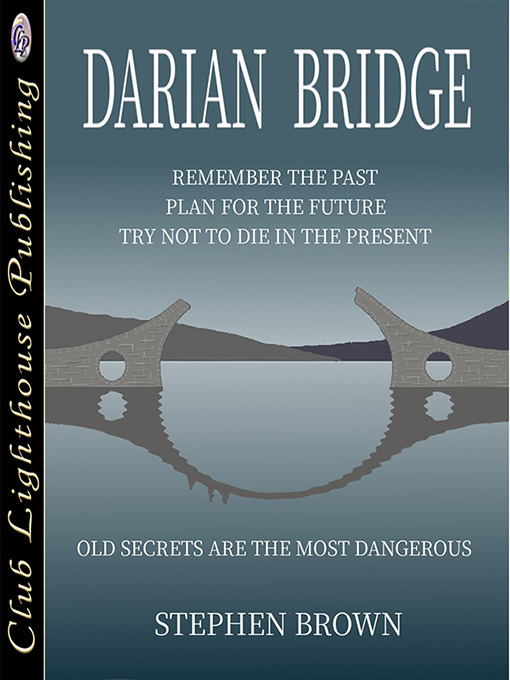

Touch image to enlarge

|

Darian Bridge

Stephen Brown

Spend no more than you make. Take no more than you can replenish. The tenets of The Austere Way movement guided three middle-European states out of the chaos of a worldwide economic collapse and to the creation of a single country that stretched from the North Sea to the Mediterranean. Fifty years later, one of its early heroes is in trouble.

|

$6.99

|

|

Henrik Glauston, retired bureaucrat, has been living a quiet, happy life with his wife, Gisela, but Gisela has just died. As a result, Hendrik has been handed his eviction notice. The cottage they occupied for half a century has been expropriated on the strength of small print in their lease. A grateful country had given them the cottage for life, a generous thanks for emergency repairs of a stone bridge in the village of Darian while the village was full of nosy, foreign reporters, but the cottage had been given to them as a couple. Now that Gisela is gone, the grateful country wants it back. Odd, because others in the same situation have not been evicted. Not so odd, because those others did not become critics of the current regime. Free of Gisela's steadying influence, Hendrik has become vocal about the present administration's failings. Don't bite the hand that holds your lease.

Hendrik will not be homeless. His old friend Klaus has a place on the north coast. The present lodger is leaving in two weeks, and Hendrik is welcome to the room. Klaus and Hendrik are old warriors from the time of the economic collapse. As students, they'd joined the teams of volunteer youths that were sent to tackle jobs that the still-impoverished government couldn't afford. Those starry-eyed youths became known as the "old guard", praised officially, dismissed as quaint by later generations. The completion of Darian Bridge occurred at the high point of The Austere Way's influence as a worldwide movement. A few weeks later, its leader was assassinated. The outside world took note and decided to recover without the strict austerity and unstable politics that seemed to be part of the Austere Way's baggage.

Hendrik has been in contact with an American journalist, Amanda Prethergill, who is writing an article about the early days of the movement. He has no concerns about helping. These are liberal times, and the present regime is more concerned with expanding the economy than agonizing over details of what happened half a century ago, or so Hendrik assumes. Negotiations are at a sensitive stage, and having a member of the old guard stirring up memories would be a bad thing, especially if he stirred up one particular memory.

Klaus meets Hendrik at the train station and asks why he's just received a visit from the Security Police. They suggested that his new tenant should be encouraged to behave. Hendrik agrees to be good. No more criticism of the present regime. No more talking to foreign reporters. Nothing but a quiet life tending a vegetable plot and cooking healthy meals.

Amanda receives a message from Klaus and it's a short one. Hendrik has been arrested for no obvious reason. Amanda is to publish nothing until the mess is cleared up.

Hendrik is being held as an Enemy of the Movement, also known as "street arrest". You've been charged, judged and found guilty. You may go about your life as usual, but there is a cell ready and waiting if you step out of line again, one that will be yours for a long time. Enemy of the Movement is an intimidation tactic. People are rarely jailed, which makes Hendrik's incarceration even more puzzling.

Klaus knows that Hendrik has been behaving since moving to the north coast. Before then he was too busy taking care of Gisela to cause trouble. Whatever happened must have happened before Gisela's illness, and the one person who would know is Gisela's sister. The sister has no idea. She phones one of her lawyers and demands he look into it. When he phones back, her reaction is to hustle Karl out of her apartment. All she'll say is that Hendrik is being held temporarily for his own safety. Leave it alone.

|

|

Length:

|

69894 Words

|

|

Price:

|

$6.99

|

|

Published:

|

Enter CD

|

|

Cover Art:

|

Stephen Brown

|

|

Editor:

|

W. Richard St. James

|

|

Copyright:

|

Darian Bridge

|

|

ISBN Number:

|

978-1-77217-273-7

|

|

Available Formats:

|

PDF; Palm (PDB); Nook, Iphone, Ipad, Android (EPUB); Older Kindle (MOBI); Newer Kindle (AZW3);

|

|

|

NO, IT WAS not unfair. The cottage had been given to us for life, but it had been given to us as a couple. Perhaps under the old guard I’d have been allowed to stay on alone, but then came the younger crowd, one that felt no obligation to the old warriors. Now we have the present gang of traitors, and you know what they’re like. Perhaps I should be grateful. The cottage was in their sights from the time Gisela moved to the nursing home. The vultures politely held off until she was dead.

I wasn’t surprised, but that doesn’t mean that I was prepared. We all live in hope. When I received the notice, hope vanished. Evicted, unwanted, thanks for your service, please go – soon. I had until the end of the month, and with Gisela only just gone I was in no condition to deal with anything. What was I supposed to do? Where would I go? I remember wandering to the front room and just sitting there watching the sun vanish over the roof tops and the sky turn dark. On the table in front of me lay the eviction notice. Gisela described our decor as post-apocalyptic drab. By the time darkness took over, that white sheet of paper was the only thing visible.

It’s a shame that you never saw our house. We call them cottages, although it’s not what you would call a cottage in your country. It was originally meant for a working man’s family, something from the time of the great factories back in the steam age. Row-houses you call them, built from blocks of grey stone, topped with black, slate roofs and jammed together to get as many as possible into as tiny an area as possible. Our row was a better class than most. Instead of fronting directly onto the road, each cottage had a tiny open area in front about the width of a kitchen table. In our early days, back when we moved in, people were still proud of those bits. Most of them were stuffed with potted flowers, a blow against the dreary, grey everything else. Each cottage had a vegetable plot in the back just big enough to grow a few spuds and a couple of lines of beets. Those tiny, productive gardens all ended at a stone wall, and on the other side of the wall was a straight drop down to the river. They call it a river, but think of a stone bed with a bit of a creek winding its way through, although I have seen it in full flood, and that is a terrifying sight. A lot of damp about as a result, but we considered ourselves lucky. Gisela and I were given the end house just where the road took a bit of a turn and jumped to the other side of the river before passing the gasworks. There wasn’t enough land to squeeze in another cottage, so in addition to our back plot we had the remaining triangular bit at the side. We used to joke that we should have registered as farmers.

I sat staring at that scrap of paper until I got hungry and found a bit of cheese and some bread. The new people don’t grow vegetables. They use the garden plots to store junk. We hadn’t given up, but when Gisela went into the nursing home I lost all interest, and I had to spend so much time travelling back and forth. By the time the eviction notice arrived, our tiny gardens had regressed to jungle. Perhaps the new occupants, whoever they are, will replant them, although it’s not the done thing now. Cheaper to get everything from a store.

I don’t know if the present regime plans to sell it or rent it. There wasn’t any hope of me taking advantage of either. We’d been just getting by when the place was ours rent-free, and with the price of real estate these days, well, you know. Same over your side, I expect. On our road there’s been quite a turnover in people. We were the last of the old guard. There was a time I knew all the neighbours. The couple next door moved in two years ago. They’ve barely said two words to us in all that time. I got the impression that the state of our cottage was depressing the value of their property. Gisela and I had planned to repaint the windows again this year. The layers of paint are probably all that holds them together. Most on the row have those new, fancy things with triple layers of coated glass and frames made of something that never needs to be painted. Someone else’s problem now.

It was too early for bed and too late to start anything. That left me a couple more hours to contemplate my future. Gisela’s state pension ended the hour she died. I’m not kidding, they calculate it down to the hour. The efficiency of the present regime’s bureaucracy is a thing to behold. With only my own pension, that didn’t leave much room to manoeuvre. Our pensions were adequate when the old guard set the amounts, but those amounts were fixed. Probably they didn’t expect us to live this long. The new lot made all the right noises about fixing the problem, but doing so never made it to the top of the priority list. The present regime, well, you can imagine.

My mother’s sister is still alive, probably due to a worldwide shortage of wooden stakes. In every family there is a driving force. My aunt is ours. When she heard that I was about to become homeless, she took great pleasure in offering the temporary use of her tiny, spare room. From the time they became teenagers my aunt and my mother disagreed about everything, including the suitability of my father. She considered The Austere Way to be an infringement on her right to destroy the planet, so when my mother encouraged me to join the movement family relations became tense. Then she discovered that the woman I was going to marry was radically into the movement. That was it. Not a word between her branch of the family and mine until the surprise offer. I have politely declined.

Gisela has a sister, a relatively wealthy one, but she considers me the worst thing that ever happened to Gisela, so no hope of help from that direction. Have no fear. I will not be homeless. The day after Gisela’s funeral I received a call from an old comrade-in-arms. He is in a similar situation. His most recent wife bailed a couple of years back and he found that life alone can be a bit much, so he took in a boarder. He must have done it for the company, because he definitely isn’t short of zdenos. The boarder was leaving in a few weeks, so I was offered the room. The morning after the eviction notice arrived I pinned the bloody thing up next to the phone to use as a note pad (old-guard thinking: waste nothing) and gave him a call. Between my eviction date and the day the room became available lay a two-week gap. His place is on the north coast, a full day’s journey on a discount-class ticket. My old life in the relatively sunny middle of the country had ended. My new life lay on the barren, wind-swept coast of the North Sea. I decided on a slow and thoughtful journey north to fill the intervening time.

|

|

To submit a review for this book click

here

|

|

|

|

|

|

|